| by Mike Matejka

The McLean County Historical Society published a 76-page book in

2000 entitled Irish Immigrants in McLean County, Illinois which

features almost 20 pages about Irish workers on the railroad. This

book is available for purchase from the McLean County Museum of

History, 200 North Main Street, Bloomington, Illinois 61701 for $12.00

which includes tax, shipping and handling.

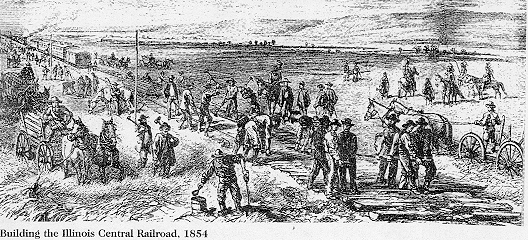

A section of the book written by Mike Matejka, Building a

Railroad: 1850s Irish Immigrant Labor in Central Illinois, discusses

the building of the Alton and Sangamon Railroad which was incorporated

in 1847. Matejka is a member of the Laborers' Union and Director of

the North Central Illinois Laborers' and Employers' Cooperation and

Trust. Long an award-winning writer, Matejka recently completed a

Master's Degree in Labor Studies at the University of Massachusetts at

Amherst.

This is Part Four and the end of the reprint of this section of

the book. Part One was printed in the November/December 2000 issue of

the BMWE JOURNAL, Part Two in the January/February 2001 issue and Part

Three in the March issue.

Disease

An infectious, bacterial disease, cholera was little understood in

1850s America. Cholera is an acute, diarrheal illness caused by

bacterial intestine infection. In an epidemic, the disease is passed

by human feces which can infect water supplies. Death can occur within

a few hours of exposure.

Asiatic Cholera appeared in the U.S. in 1832, brought to Illinois

that summer by troops coming for the Black Hawk Wars. The disease was

not a constant, but appeared irregularly, with another upsurge in

1849-50. Various ineffective patent medicines were sold for its relief

and the disease was frequently blamed on "miasmas," hot

weather or swampy conditions. Although these early medical theories

pointed to conditions where brackish water could nourish bacteria, the

connections were not apparent in the 1850s. It was a feared disease,

not understood, whose outbreak could frighten a community. In 1850

Bloomington residents were warned the disease had broken out again.

Chicago lost 1,184 residents in 1854 to a cholera outbreak. The 1850s

newspapers report not only local outbreaks, but outbreaks in other

communities. In some cases, the names of local residents infected are

named, but immigrants are often referred to simply by their ethnic

origin, as the Bloomington Weekly Pantagraph reported five cholera

deaths in August 1855, noting among the victims "Mr. Joseph

Clark...three of the others were Germans, one man and two women, and

the other was an Irish woman." The speed of cholera infection is

apparent from an 1852 Bloomington Intelligencer piece about the death

of William Hodges, a young man in his 30s:

The deceased arrived here in the Peoria stage, on Friday evening,

apparently in the enjoyment of his accustomed health, and on Saturday

morning breakfasted with his friend, Mr. Hodges, as heartily as usual.

About seven o'clock, the diarrhea, which had been arrested the

previous evening, returned with such increasing violence, that

notwithstanding the administration, by skillful and experienced

physicians, of the most efficient remedies, aided by the assiduous

attentions on the part of those who assisted in waiting upon him, the

nine hours thereafter, this terrible disease had runs its course, and

its victim lay a lifeless corpse!

Amongst the newspaper reports are frequent mention of cholera

outbreaks in work camps along canals and railroads. The Weekly

Pantagraph noted a story from the Galena Jeffersonian in August 1854

about 150 rail laborers that died of cholera in Galena. The contractor

encouraged his workers to flee, but even with that half of them were

killed. Reflecting current medical theories which blamed cholera or

bad air or "miasmas," the newspaper wondered how these

deaths could take place 450 feet above the Mississippi in a place with

"ground dry and air pure." The Illinois Central lost 130

workers at Peru in two days in 1852, delaying construction of an

Illinois River bridge. The social separation between established

settlers and immigrant rail workers is apparent in an 1852 Weekly

Pantagraph article, reprinted from the St. Louis Intelligencer, that

notes rail worker cholera deaths in the LaSalle-Peru area, but

reassures the reader that the established community is safe:

CholeraŚWe regret to learn from the offices of the Regulator that

the cholera has again made it appearance among the laborers on the

railroad and public works in the neighborhood of Peru on the Illinois.

Sixteen deaths had occurred, nine at Peru and seven at LaSalle. None

of the citizens had been attacked, and no great alarm was felt of the

disease spreading to any great extent.

If the area newspapers mark cholera deaths, did the workers buried

at Funks Grove die of cholera or some other cause? Why are there no

newspaper notices of epidemics along the rail line building into

Bloomington? The answer is unknown. The only existing records are the

1920s cemetery map, which marks the Irish workers' burial, and the

local oral tradition, which notes the workers' death and mass burial.

Two possibilities exist: one, the workers did die of cholera,

dysentery, or some other infectious disease. With a new rail line

building into Bloomington, the local papers ignored the deaths,

fearing stirring up fear or fermenting a negative image of the new

rail line. Or, because immigrant deaths were so common, as the other

reports note, their deaths were beyond official recognition. Or, a

second possibility is that the workers died not at once, but in

smaller groups. Because of the Funk Family's generosity in sharing

their cemetery space, the workers had an official burial spot, rather

than scattered track side graves. Thus workers over an extended period

could have been added to those already interred at Funks Grove. The

existence of two separate burial spots in the cemetery records may

point to two separate, or multiple internments. The Funk family broke

social barriers of the times in allowing Irish burials in their

cemetery. Bloomington did not have a Catholic Church until 1853 and a

cemetery until 1856. The reigning mayor, Franklin Price, was a

"Know-Nothing," frequently attacking the growing Irish

community on Bloomington's west side. Perhaps the Funks Grove cemetery

was a sanctuary for the growing Irish community, until they were able

to establish their own burial spot, outside city limits, in 1856.

Frequent cholera outbreaks in work camps, mentioned in newspaper

dispatches during this era, could have been another source for

anti-immigrant antipathy. Immigrants coming into town could have been

classified and stereotyped as disease carriers.

Whatever the immediate facts, there was undoubtedly some solace to

these workers in a burial in an established cemetery. Immigrants in a

strange and unwelcoming land, death was an immediate reminder to these

workers of their poverty and isolation. Carl Sandburg quotes a song

fragment in his 1920s "American Songbook," which echoes the

experience of many early rail workers:

There's many a man killed on the railroad, the railroad, the

railroad.

There's many a man killed on the railroad, and laid in a lonely

grave.

Fifty years later Macedonian immigrant Stoyan Christowe rememberd

burying his father on the Great Plains, while working in Montana for

the Great Northern Railroad. Christowe went on to success as an author

and eventually a Vermont State Senator, but his poignant remembrance

echoes what the 1850s Illinois Irish workers might have felt:

Slowly and silently the band of men moved across the open plain

behind the coffin of rough pine boards borne by a farmer's cart. The

farmer on the driver's seat, with his team of horses, along seemed of

this place. ....

The procession through the treeless plain was unreal and

unbelievable. There was something incomplete, unfinal, about my

father's death, and about his burial. This was no way to return a man

to his eternal resting place. No bell tolled; no priests in vestments

swung fuming censers or intoned funeral chants. And there was no

avenue lined with tall populars and cypresses leading to a chapel

shaded by ancient oaks and walnut trees. ...How my father would grieve

if he knew that he had become the cause of every man in the gang

losing a day's wages in order to bury him.

Resistance

Although facing adverse conditions, immigrant workers did not

passively accept their situation. Already used to dogged resistance to

British colonial rule and fights with absentee landlords, immigrant

workers struck against poor working conditions or to force wage

payment. In examining over ten work stoppages on the Chesapeake and

Ohio Canal between 1834-40, Peter Way credits the Irish work force

with resistance skills polished for centuries against the English,

transferring those skills to the American wage system: "The

methods the Irish had developed at home, secret societies and

collective violence, were imported to the New World and adapted to its

developing capitalist social system. Although not necessarily

organizing trade unions, the early laborers depended upon collective

action to right a perceived injustice. Since the rail and canal

companies often used contractors for construction, these actions were

often taken against contractors who were perceived to be unfair or who

shorted workers' pay. Ethnic unity helped maintain a code of secrecy,

where workers often took violent retribution against unpopular

contractors or foremen. This is not to say the workers were

continually violent, but did react to a perceived injustice. The

already constructed Baltimore & Ohio Railroad complained in the

1850s that Irish workers not only mobilized for higher wages, but also

to protect their job security and would not permit the company to

replace them with other workers.

Although submitting to the arduous work day on the railroad,

laborers did respond when faced with an unjust condition, usually with

a refusal to work, or often an outbreak of violence. In April 1853, as

the A&S was building from Springfield to Bloomington, there was a

strike, workers demanding $1.25 per day. When one gang refused to join

the walk-out, a fight ensued. The Springfield Daily Journal reported

that "Nobody was killed, though blood flowed freely and legs done

their duty." Hauled before the local magistrate, the workers

maintained their secrecy and their solidarity, refusing to answer

questions. One worker was sentenced to jail on contempt charges for

this refusal. The papers are quiet as to an outcome, whether or not

the higher wages were won, or whether any workers were dismissed over

the issue.

That winter there was an outbreak of violence on the Illinois

Central in LaSalle on December 15, 1853, after a contractor, A.J.

Story refused wage payment. He was attacked by a group of workers and

murdered after he shot an Irish worker. Supposedly $5,000 was taken

from Story's safe and distributed amongst the waiting workers.

Approximately 600-700 Irish workers filled the city's streets, until a

local militia marched on them and dispersed them. Thirty-two workers

were imprisoned the next day, followed by another 150 after the local

police spent the night searching Irish shanties, with one man wounded

when he refused arrest.

This resistance continued, even after the rail lines were

completed. As the A&S line was completed to Chicago in 1959,

workers again struck. This time the predominantly Irish surname

workers were not track layers but were engineers, firemen and

conductors. The company was in precarious financial condition and the

workers protested a wage cut and payment in low-value company script.

In 1863 Bloomington workers were amongst the founders of the

Brotherhood of Footboard in Michigan, which became the Brotherhood of

Locomotive Engineers. Irish immigrant son Patrick H. Morrissey of

Bloomington would salvage the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen as

their Grand Chairman, after the 1894 Pullman strike, rebuilding tha

organization and stabilizing its membership.

Conclusion

Immigrant workers, facing a strange land, brutal working

conditions, and unhealthy living conditions, survived through their

hard labor and their collective support of each other. The mass grave

at Funks Grove Cemetery is a stark reminder of the harsh condition

these workers faced. Although a difficult situation, these workers

survived through systems of mutual support. Through this they

developed their systems of resistance, learned survival tactics and

laid the foundation for later generations which would profit from

their experience and legacy to win full citizenship and rights in

American society. |