Labor Day rightfully belongs to the workers who toil diligently day after day to

contribute their share to fulfilling the needs of man.

Long before Labor Day became a legal public holiday it was celebrated by workers as a

day of festive activity and rest from their daily tasks. It was the creation of laborers,

not of politicians. It was the brain child of a union carpenter 12 years before Labor Day

was proclaimed a U.S. national holiday by act of Congress.

The carpenter, Peter J. McGuire, a native of New York City, who joined the ranks of

America's toilers while still a child, is recognized as the father of the observance in

honor of his country's working people.

In 1882, he stood before the newly organized Central Labor Union of New York City and

proposed that one day of the year be set aside as a general holiday for the working

masses. He suggested that the holiday be known as Labor Day and that it be set for the

first Monday in September, which would put it midway between two U.S. national holidays --

the fourth of July and Thanksgiving. Other delegates to the meeting enthusiastically

embraced the idea. A committee was named and soon preparations were under way for the

initial celebration of Labor Day.

That may have been the first U.S. Labor Day celebration, but the records say the

beginnings of the day's observance probably go back to demonstrations by Canadian

unionists in 1872.

In that year, mass campaigns were organized to gain freedom for 24 jailed leaders of

the Toronto Typographical Union, which was on strike to obtain a nine-hour day. In Ottawa,

Daniel O'Donoghue, a printer, and Donald Robertson, a stone mason, organized a mile-long

parade to the home of Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald to obtain from him a promise

that Parliament would abolish the laws which made trade unions illegal. The laws were

rescinded that year and Canadian unions finally won legal recognition. They were no longer

considered by law as criminal conspiracies in restraint of trade.

To mark labor's new-found status, the Toronto Trades Assembly put on a parade and

celebration, which became an annual event.

In 1882, the Toronto Trades and Labour Council -- the new central labor body --

scheduled a Toronto demonstration and parade for July 22 and asked McGuire to appear.

Illness in his family kept him away, but, it is said, the Toronto affair gave him his idea

for a U.S. Labor Day and the New York City parade that was held later in the year.

In Canada, during the remaining 1880s, Labour Day was made a holiday by many

communities and the Trades and Labour Congress repeatedly sought formal federal

recognition of its celebration. Finally, in July 1894, the Parliament declared the day an

official annual holiday.

In the United States, approximately two years after the first observance of Labor Day,

the 26 delegates to the fourth annual convention of the American Federation of Labor held

in Chicago adopted the following resolution:

"Resolved, That the first Monday in September of each year be set apart as a

laborers' national holiday, and that we recommend its observance by all wage workers,

irrespective of sex, calling or nationality."

During the next few years organized labor devoted its attention to securing state

legislation making Labor Day a legal holiday. As early as 1887, Oregon enacted the first

state law, but this measure designated the first Saturday in June as Labor Day. This was

changed to the first Monday in September in 1893. Ultimately, 23 states proclaimed Labor

Day a legal holiday.

The Labor Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives in May of 1894 presented a

favorable report on a bill making Labor Day a legal public holiday. By June 26 of that

year Congressional action on the bill had been completed and two days later the measure

was signed by President Grover Cleveland. The pen used by the President was turned over to

Representative Amos J. Cummings of New York City, who sponsored the bill in the House.

Cummings then sent the pen to President Samuel Gompers of the American Federation of

Labor.

Thus, a dozen years after McGuire first advanced the idea of a special holiday honoring

labor before the Central Labor Union of New York City, the proposal had the approval of

the American people, expressed through their elected representatives at Washington.

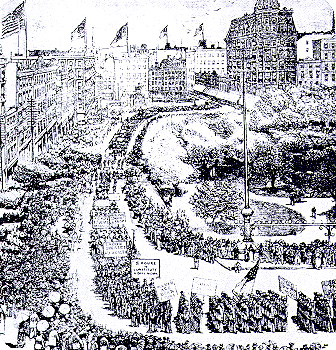

Newspaper accounts have preserved for us the color attendant upon the celebration of

the first Labor Day in New York City when organized labor paraded in orderly fashion

through the streets of the city.

Of the picnic in Elm Park following the parade, one newspaper said:

"It had been arranged that each union would have a certain portion of the grounds

marked out for itself, and this facilitated a greater fraternizing than otherwise could

have been observed.

As it was, fellow workers and their families sat together, joked together and caroused

together ... they all hobnobbed and seemed on a friendly footing, as though the common

cause had established a sense of closer brotherhood."

From mid-afternoon to nightfall there was speech-making. One of the best received

speakers was McGuire himself.

With evening came a still larger crowd, for only a fraction of the city's employers had

decreed a holiday, and the Central Labor Union had advised all whose employers desired

them to work to do so. Fireworks and dancing both had important parts in the night's

festival.

Over the years since 1892 much has been said concerning the significance of Labor Day.

One of the best statements was made by Samuel Gompers, President of the American

Federation of Labor, in an editorial written 79 years ago for the American Federationist.

While the reference of the 19th Century is remote, Gompers remarks are timeless in point.

He wrote in part:

"No one day in the calendar is a greater fixture, one which is more truly regarded

as a real holiday, or one which is so surely destined to endure for all time, than the

first Monday in September of each recurring year, Labor Day.

"Labor Day differs in every essential from the other holidays of the year of any

country. All other holidays are, in more or less degree, connected with conflicts and

battles, or man's prowess over man, or strife and discord, or greed for power, or glories

achieved by one nation over another.

Labor Day, on the other hand, marks a new epoch in the annals of human history. It is

at once a manifestation of reverence for the struggles of the masses against tyranny and

injustices from time immemorial; an impetus to battle for the right in our day for the

men, women and children of our time, and gives hope and encouragement for the attainment

of the aspirations for the future of the human family.

Reprinted from BMWE Journal September 1965. |