|

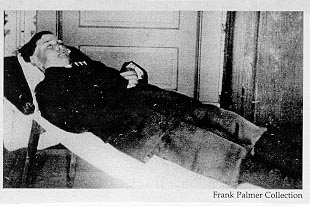

Eleven-year-old William Snyder Jr., April 22, 1914.

Year after year coal miners died violently and frequently in

Colorado mines. Hazards in early Colorado mines doubled fatality rates

everywhere else in the world. The high death tolls reflected gross

negligence on the part of coal companies concerning mine safety.

Miners living conditions were primitive and they were forced to

live in fenced camps patrolled by armed guards. Workers were paid in

"scrip" which was good only at a company store.

When mine owners were criticized for their brutal treatment of

workers, they reminded their critics that the miners were only

"ignorant, lawless and savage South European peasants." Coal

camps were viewed as "little United Nations of the poor"

where "foreigners were seen as a threat because of the unrest in

Europe that led to World War I a few years later."

Union organization was slow. It was not easy for union

representatives to enter fenced mine camps patrolled by armed guards.

But by the end of 1911, "a complicated spy network operated in

the southern coal fields." Union organizers worked in the mines

to recruit members but company spies worked just as hard to locate

union organizers. Union miners were fired, tarred and feathered,

threatened, beaten, and/or rounded up and taken across state lines and

abandoned in remote areas without any supplies. Still the union

movement gained strength.

In 1913, miners drew up a list of demands and presented them to the

coal mine owners:

Recognition of the union.

A raise in wages.

An eight-hour day.

Pay for dead work (brushing, timbering, laying rail, etc.).

A weigh-man at all mines elected by the miners.

Right to trade in any store they chose.

Right to choose their own boarding places and doctors.

Enforcement of the Colorado mining laws.

Abolition of the guard system.

When the owners ignored the miners' demands, the United Mine

Workers of America called for a strike on September 23, 1913. After

they were evicted from their company housing, some 10,000 miners moved

to tent colonies established by the UMW on land rented by the union

east of the coal camps. As miners and their families moved into the

tent cities in locations near Aguilar, Forbes, Ludlow, Starkville and

Walsenburg, they were confident the mine owners would soon meet their

demands.

But the mine owners had no intention of even considering the

workers' demands. They hired more "Baldwin-Felts

detectives," doubled the guards around company property,

purchased large quantities of rifles and ammunition and demanded the

governor send in National Guard troops to protect mine property.

"Using troops to favor the position of coal companies was

illegal, but it was a practice that went on in Colorado for many

years."

The Rockefeller-owned Colorado Fuel & Iron steel mills in

Pueblo, Colorado even built a unique armored car for the company.

"With bulletproof sides and machine guns mounted in the back, it

was nicknamed the ‘Death Special' by miners because the gunmen who

used the car took perverse delight in spraying bullets through the

tents as they roared past the colonies. At the Ludlow camp, men dug

holes under the tents to protect their families from the flying

bullets that tore through their canvas homes."

"The winter of 1913-14 was one of the worst recorded in

Colorado history. Mountains of heavy snow piled up in the streets. The

canvas shelters were cold and often wet. Hunger stalked the families.

The men hunted daily, and if lucky, added a rabbit or deer to their

skimpy menus."

By spring the financial burden of keeping troops in the field was

bankrupting the state and as members of the regular National Guard

grew tired of the long tour of duty and asked to be replaced, more

coal company gunmen began appearing in uniform. On April 14, 1914, the

Colorado governor withdrew all but two outfits of troops from the

field. The two troops left, made up mostly of company men, mine guards

and gunmen, were stationed near Ludlow, 18 miles north of Trinidad.

On Easter night (April 19), company-employed gunmen and members of

the National Guard drenched the strikers' tents with oil and brooms

dipped in kerosene. Before dawn, they ignited the tents while the

miners and their families were asleep. When the miners, their wives

and their children ran from the burning tents, they were

machine-gunned. Many escaped in the darkness, many were wounded, but

five men, two women and 13 children died.

Eleven of the children and the two women, one pregnant, died in a

dugout under one tent where they had taken refuge but instead died of

suffocation. Eleven-year old William Snyder Jr. was killed instantly

by a bullet to the head when he left the protection of the dugout to

get water for his mother. The site was soon christened "The Black

Hole of Ludlow."

(When the UMW built the Ludlow monument in 1918, it was placed

directly east of the Black Hole. The pit itself was cemented in with

stairs going into the hole where the women and children perished

during the massacre. A trap door seals the pit from the elements, but

it can be opened and visitors may go down into the hole.)

Mine owners quickly issued statements charging the striking miners

with "starting the fight at Ludlow" and maintained an

overturned stove started the fire that killed the women and children.

They blamed "cheap professors, even cheaper muckraking magazines

and a lot of milk and water preachers" for making a mountain out

of a mole hill with the story of the massacre.

John D. Rockefeller, Jr., however, took full responsibility for the

massacre, saying it "was the unfortunate outcome of a principled

fight he was bound to make for the protection of the workingman

against trade unions."

(Sources: Labor's Untold Story, Richard O. Boyer & Herbert M.

Morais, and "Remember Ludlow," Joanna Sampson.)

|